One concern, sometimes expressed in the literature, is that precision medicine with its emphasis on the genetic distinctness and treatment of many cancers will create “genetic tribes,” which threaten solidarity.

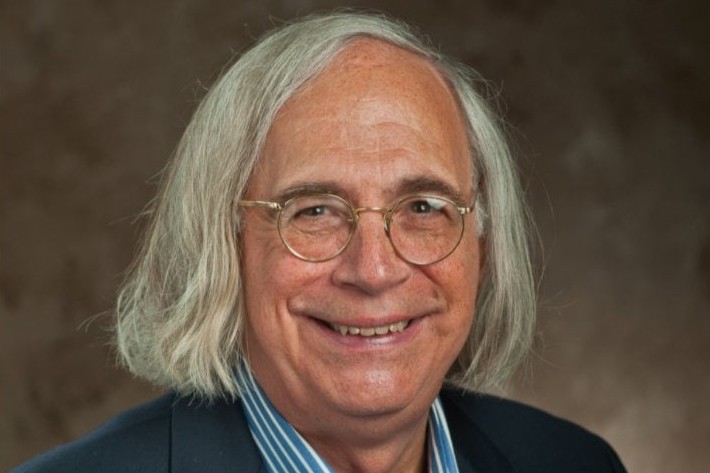

Len Fleck (University distinguished professor and past director of MSU’s Center for Ethics and Humanities in the Life Sciences), along with two European partners, will be hosting a three-day workshop funded by the Brocher Foundation outside Geneva Switzerland, from May 18-22, 2026. This workshop is limited to twenty invited presenters. Papers based on those presentations will be published in an edited volume by Springer.

Principal Investigators:

Leonard M. Fleck, Michigan State UniversityEline Bunnik, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre Rotterdam

Jilles Smids, MC, University Medical Centre Rotterdam

KEY PROJECT QUESTIONS

In European countries with publicly funded healthcare systems, the rise of precision medicine is increasingly causing concerns about affordability and financial sustainability. New and innovative drugs, including cell and gene therapies, are entering the market with unprecedented upfront costs. While some of these hyper-expensive drugs are considered therapeutic breakthroughs, there is often some level of uncertainty regarding the extent and duration of their effects. For these reasons, national institutes tasked with healthcare priority setting may – justly – be reluctant to provide unrestricted access to new therapies that are insufficiently cost-effective, using public resources. While such institutes have traditionally used cost-effectiveness in patient (sub-)populations as a criterion for coverage decision-making, the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) increasingly facilitates the evaluation of cost-effectiveness at the level of the individual patient. For example, many patients with various advanced hematologic cancers would be eligible for CAR T-cell therapy with a front-end cost of €475,000. AI might be applied to make prognostic and predictive judgments about CAR T-cell treatment outcomes in individual patients. We know statistically that 30% of treated patients will fail to gain an extra year of life. The other 70% may gain one to four extra years of life. Is it congruent with solidarity, or justice, to use AI to identify those 30% patients and deny them CAR T-cell therapy because it would clearly not be a cost-effective use of social resources? Also with gene therapies, most of which are extraordinarily expensive, with costs of €2 million to €3.5 million for one-off treatment, some patients may experience lifetime therapeutic effects, while in others, as suggested by emerging evidence, therapeutic effects will diminish over the years, maybe over 3 to 8 years. Would a patient with only a three-year therapeutic effect not have a just or solidarity-based claim, to another round of gene therapy at a cost of €3 million? If AI had this degree of reliability, would it be ethically permissible to use AI to make these rationing decisions, or, in order to sustain the public healthcare system, might it be even ethically obligatory?